Four Cylinders; Five Decades of Modernity

The story of the world-famous BMW Headquarters in Munich is one of innovative spirit, architectural vision, and new ideas in times of great change. As the building turns 50, we look back at how it came to be – and what it has come to represent.

It’s a familiar sight to locals as well as returning visitors to Munich: the BMW Headquarters, located in the north of the city, just a stone’s throw from the Olympic Stadium, and with the German Alps rising behind it. For over 50 years, the famous building has been a central part of the Munich cityscape and remains an icon to this day.

To truly understand the story of the “Hochhaus” (as the building is known to most employees), we need to understand its role in the history of the company and the BMW brand. And not least how its construction and opening coincided with an epoch of unparalleled development, marked by profound and rapid change.

A LEAP INTO MODERNITY

The late 1960s were a time of great success for BMW. Sales were growing significantly under then chief sales and marketing officer Paul G. Hahnemann, and it soon became clear that the time was ripe for expansion. To meet the growing demand for BMW vehicles, Hans Glas GmbH – a competitor located in Lower Bavaria – was purchased in 1966, adding production plants in Dingolfing and Landshut to the home plant in Munich. But it quickly became clear that administrative space for the company’s Munich-based employees was forming a bottleneck for further developments.

The late 1960s were a time of great success for BMW. Sales were growing significantly under then chief sales and marketing officer Paul G. Hahnemann, and it soon became clear that the time was ripe for expansion. To meet the growing demand for BMW vehicles, Hans Glas GmbH – a competitor located in Lower Bavaria – was purchased in 1966, adding production plants in Dingolfing and Landshut to the home plant in Munich. But it quickly became clear that administrative space for the company’s Munich-based employees was forming a bottleneck for further developments.

In 1968, a call for submissions was sent out to architects to present their visions for a new office space to be located in Munich. The winning design came from architect Karl Schwanzer, who in this way became the mastermind behind the “Hochhaus”.

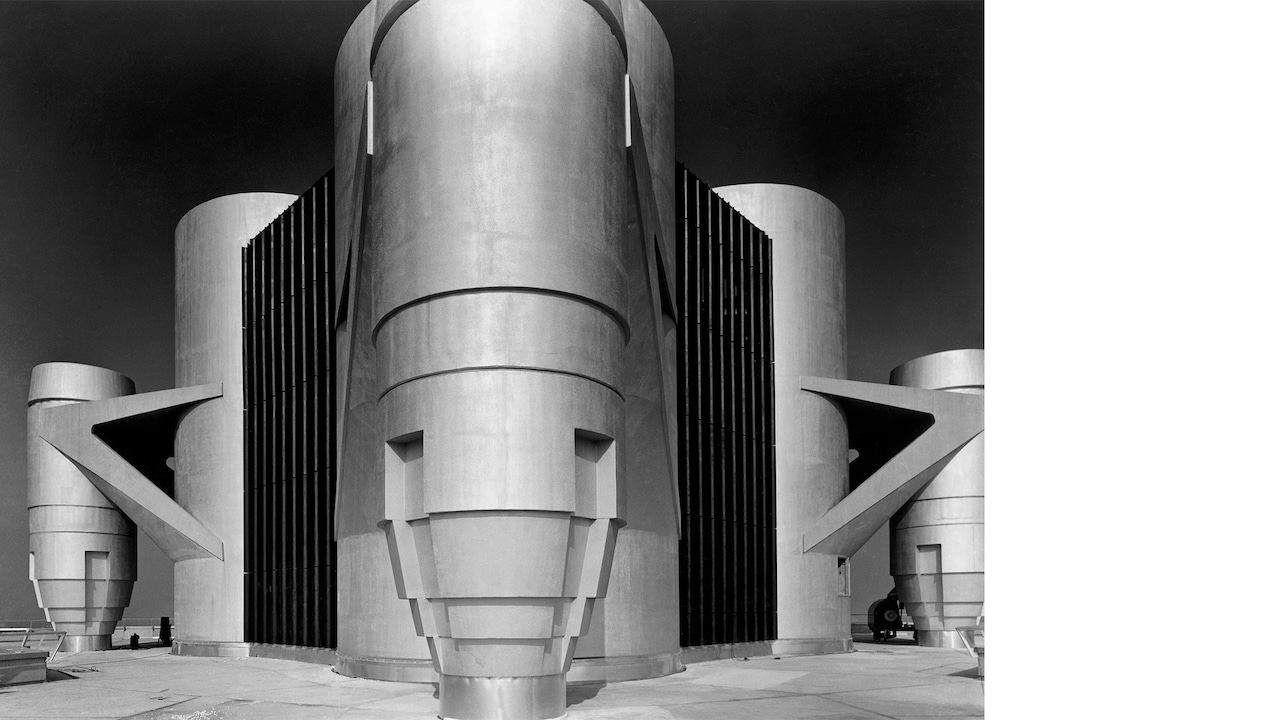

Schwanzer’s plan for the building was truly revolutionary. The Vienna-based architect envisioned an architectural landmark for the city of Munich, consisting of 22 levels of offices, board rooms and a basement, standing 99.50 meters (around 327 feet) tall and centered around four symbolic cylinder-shaped main elements. His idea, however, was more than glossy symbolism. Schwanzer, clearly inspired by Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer’s approach to the duality of form and functionality, stressed the need for modernly designed office spaces for seamless communication and coworking between employees, as well as an exterior that reflected the company’s trademark characteristics of clearly shaped precision engineering, technical prowess, and financial success. Thus, the extraordinary design language laid out in his proposal would not only reflect BMW as a company at the forefront of automotive innovation, but also offer practical benefits to the many employees who would frequent the new headquarters for work every day.

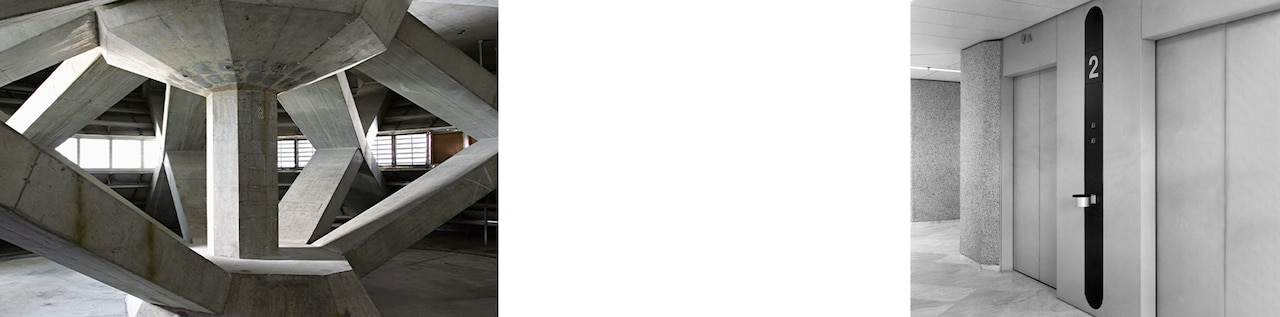

Technically, the building was a marvel too. Instead of being built on a traditional foundation, Schwanzer’s vision saw it hanging from a cross-shaped steel structure. Consequently, the almost 100-meter-tall building wasn’t to be built from the bottom-up, as is usually the case, but constructed “from above”; the upper floors were to be built first, “hanging” from the steel roof construction, while the four cylindrical main elements were to be created on the ground, then moved upwards hydraulically and completed in segments. As a method, this was almost unheard of in the late 60s and only further illustrated the futuristic and innovative nature of the new headquarters.

After this admittedly ambitious vision initially polarized, an agreement was eventually reached, and construction began in late 1968. Four years later, just as Munich opened its doors for the 1972 Olympic Games, the new building was finally completed, followed by the official inauguration on May 18, 1973.

An underlying motivation for this enormous investment was also to signal the company’s readiness for the coming years. In this way, the opening of the new headquarters – just as the world’s most gifted athletes competed for Olympic medals practically around the corner – was highly symbolical: With it, BMW was sending a clear signal to the world that it was ready to up the ante and make a push into modernity, with no compromises.

The 1970s ushered in unprecedented changes and an uprooting of cultural, societal, and financial paradigms, and BMW was no exception to this. While the 60s had laid the foundation for an unprecedented expansion and growth for the business, when Eberhard von Kuenheim took over as CEO in 1970, things really took flight. Under his tenure, BMW took several steps to future-proof the business, many of which are still fundamental to the company’s success today. A new and flexible plant expansion strategy made sure that production wasn’t bundled centrally, but through a highly flexible production network.

It was also under von Kuenheim’s early years at the helm that a new naming for the BMW model lineup was introduced with the 3, 5 and 7 Series designations, a concept so future-proof that its principles are still working today. The board of directors decided on the numbering of the existing model lines, deliberately leaving space between, above, and below the numbers for future models and series, thus ensuring possibilities for expansion and extension without later having to reconceptualize the famous denominations.

The finishing of the “Hochhaus”also coincided with another milestone in BMW history: the presentation of the company’s first-ever fully electric vehicle, the BMW 1602e. This concept vehicle, built on the technical basis of a regular BMW 1602, played a central role in the 1972 Munich Olympic Games. Sporting an all-electric range of a little more than 50 kilometers and a top speed of about 50 km/h, two of these specially built BMW vehicles led the Olympic athletes in the marathons and long-distance events, sped through race courses at the games, and made a media splash with their sporty looks and characteristic bright-orange paint job. But more importantly, the BMW 1602e showed the world that it was possible to design and build a car powered entirely by electricity through batteries… a feat which cannot be underestimated today, 50 years later, at a time where BMW is leading the push towards electrification with a full line-up of all-electric premium vehicles and several new models in the pipeline over the next couple of years.

“GEBAUTE KOMMUNIKATION”

As the BMW Headquarters turns 50, Professor Karl Schwanzer’s design and architectural vision continues to mark and symbolize BMW’s architectural philosophy. With the building that came to define his legacy, Schwanzer had imagined a truly modern working environment, with optimal conditions for the employees who would work on the many products and concepts that have defined BMW success ever since: Bright, large office spaces in circular rooms meant that most workers had desks close to the windows, while corridors running through the core of the building meant that no one had to run through working areas when moving from one department to another. And with an exterior that was at once impactful, symbolic, and modern, the new headquarters not only instantly left its mark on the Munich cityscape; it also signaled a new era of innovation and modernity for BMW as a business to the outside world.

This merger of form and function has since been dubbed “gebaute Kommunikation” – or constructed communication – hinting at the building’s ability to combine practical solutions with strong messaging and clearly shaped symbolism. As a principle, this has since been a cornerstone in the BMW approach to design and architecture and has significantly impacted the construction of other landmark building projects.

Shortly after the opening of the BMW Headquarters in 1973, the new BMW Museum right next to the “Hochhaus” opened its doors.Like the new headquarters, the museum was drawn by Professor Schwanzer, who imagined the museum’s famous bowl-like design and interior concept – ideal for BMW to showcase its technological and engineering highlights from the past, present, and future to curious visitors from the public. Since then, more now-iconic BMW buildings have followed that same architectural philosophy as they were built, like the FIZ – the BMW Research and Innovation Centre –, the Zaha Hadid-designed central building of the Leipzig-based production plant, and the BMW Welt. The creative mind behind their design was Wolf D. Prix, co-founder of the architectural cooperative Coop Himmelb(l)au and one of the most important representatives of deconstructivism – and a student of Karl Schwanzer.

Today, the BMW Headquarters remains a central piece of the BMW cosmos, frequented by countless BMW employees every day, who benefit from Professor Schwanzer’s visionary take on a modern working space. Since those opening days, the building has undergone a thorough process of restoration from 2004 to 2006, after receiving official protected status in 1999.

Today, the BMW Headquarters remains a central piece of the BMW cosmos, frequented by countless BMW employees every day, who benefit from Professor Schwanzer’s visionary take on a modern working space. Since those opening days, the building has undergone a thorough process of restoration from 2004 to 2006, after receiving official protected status in 1999.

As the building heads on to its next decades, it will continue to mark BMW development and serve as a powerful reminder of how the company entered modernity in ways that are still to be found and felt today, and will be for a long time to come.